Thanks to the wonders of Internet and WordPress, any company can rationalize the cost of digital publishing.

What’s more, Google’s decision to communicate the dialing down of activities in China on its corporate blog gave street cred to owned media. Since Google’s act on January 12, 2005, organizations of all shapes and sizes have become much more aggressive in taking their stories directly to the target audiences.

There’s no question that this move lessens dependence on third-party media. Like the investment world’s emphasis on the diversified portfolio, the building of a brand calls for diversified activities.

With that said, the value of media relations doesn’t disappear. In today’s environment where information gets flung about with the care of a ditch digger, one could make an argument that media coverage is more valuable than ever to a brand today.

Yet there’s the rub.

Succeeding with journalists can require NOT publishing. In fact, it can often mean not publishing your best stuff.

It sounds counter-intuitive, but you can see how this plays out with Intel’s recent media relations work to publicize the 50th anniversary of Moore’s Law.

Intel essentially takes on the role of journalist in interviewing Gordon Moore on his famous axiom. Rather than publish the interview, Intel opts to package the content in a tidy PDF downloaded from its newsroom.

In pointing journalists to the content, Intel gains three benefits:

- “Access” to new perspectives from Mr. Moore stands to increase the depth of the stories.

- Inserts Intel’s preferred narrative slices into media stories.

- Controls Mr. Moore’s input (also reduces the demands on his time).

Let’s look at this last point. Even if Intel ponies up Mr. Moore for a day or even two days of press interviews, you’re still going to have a gaggle of journalists indignant that they weren’t the chosen ones.

Some journalists like Don Clark at The Wall Street Journal tried to connect with Mr. Moore: “Mr. Moore couldn’t be reached, and Intel said he wasn’t available to comment.”

Of course, everyone ends up unhappy if Intel manufactures 1,500 words of corporate speak. To this point, there’s a journalistic-like quality to the Intel deliverable with the same storytelling techniques.

For example, this anecdote surfaced in the BBC and The Wall Street Journal:

- “It’s amazing how often I run across a reference to Moore’s Law. In fact, I Googled ‘Moore’s Law’ and I Googled ‘Murphy’s Law’ and ‘Moore’s Law’ beats ‘Murphy’ by at least two to one.”

There’s very much a conversational tone to much of the content like this passage that landed in the San Jose Mercury News and PC Mag:

- “But one could see the trend was going in the direction that this was going to be the cheaper way eventually. That was my real objective — to communicate that we have a technology that’s going to make electronics cheap.”

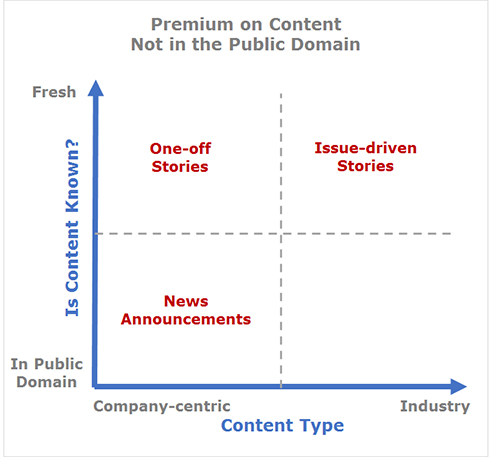

Back to the point that Intel did not publish the Moore interview. The commoditization of the news release forces journalists to dig deeper for stories and content not in the public domain.

It’s true that the Intel document sits in the public domain (Intel’s press room). Still, by virtue of the packaging — atomized content instead of a complete story — and being “roped off” for journalists, the perception is one of out of the mainstream view.

Did Intel’s approach work?

The question can’t be answered by simply looking at media impressions. The media was going to cover a milestone of that magnitude whether Intel lifted a finger or not.

But given that Intel’s atomized content showed up in so many of the articles ranging from USA Today to CNET to Wired, it seems reasonable to conclude that Intel accomplished its mission.